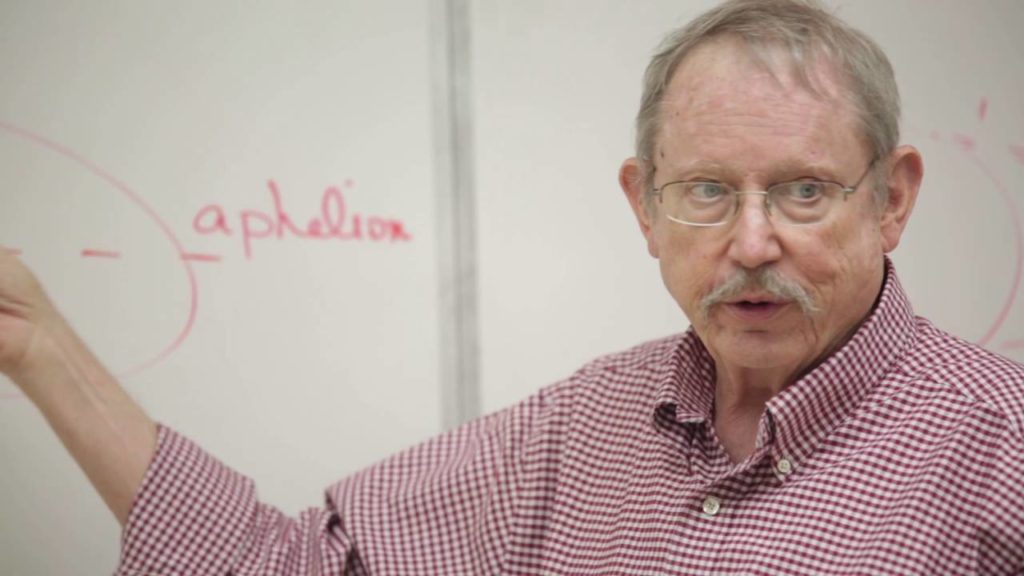

In our last newsletter we marked an important world event: the International Asteroid Day, which takes place every year on 30 June. This time, we talked to Patrick Miller, the director of the IASC, who in a friendly chat told us a bit about himself and the citizen science programme focused on the asteroid search of which he is director and founder.

Dr. Patrick Miller is a Professor of Mathematics at Hardin-Simmons University, Texas, USA. He founded the International Astronomical Search Collaboration (IASC) in 2006, after he and one of his students took the initiative to do something for outreach and informal education in astronomy.

They had heard that the Hands On Universe organisation was conducting asteroid searches in the early 1990s, but that programme lasted only a few weeks. They thought about starting it up again, which they did in October 2006. At that point, not everything went well, and after some adjustments, the project started to grow.

Over the years, IASC has developed significantly. The first campaign they launched involved five schoools, but now more than 6,300 schools are involved, located in 89 countries. So, near 40,000 students around the world participate in the asteroid search every year. To give an idea, since January 2019 students have found more than 10,000 very faint asteroids that were not reported by sky surveys, but by the students. This is of interest to NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office. Of the 10,000 that were found, 1% were Near Earth Objects candidates, which means Earth threatening candidates. This is a good parameter to evaluate the IASC, its usefulness and utility.

Patrick Miller explained to us that the main aim of the programme is to empower teachers. As a natural result of teachers bringing the project into the classroom, students can actually make original discoveries, using real data, and be excited about science and astronomy.

For the IASC director, the programme can be easily incorporated into the formal educational environment, “I use it in my teaching classes, and teachers can use it as an educational tool, and they do. It’s very exciting to think that you may do a discovery and that discovery may be named after you, so it’s more than just introducing science into the classroom is using astronomical data to make original discoveries.”

For informal education programmes to succeed in formal education, they have to demonstrate that they fit certain curriculum needs, Miller said. IASC is a tool for teachers and relies on the teacher to integrate it into their classroom in the way they feel best suits their curriculum. Suggestions are offered on how teachers can do this, but ultimately that responsibility lies in the hands of the teacher.

IASC has been included in the astronomy curriculum in Germany, and also negotiations at government level in Brazil and India, for example, have resulted in bringing this informal educational project into formal settings.

Although primarily referred to as an informal education programme, since 2018 the project has received funding from NASA in the context of citizen science, which has allowed it to expand by considering teachers and students as active stakeholders in citizen science.

For us, there is no doubt about how IASC is a unique initiative that is expanding and reaching thousands of schools and with the capacity to expand further, showing how doing science is within everyone’s reach.

More info on Dr. Patrick Miller and IASC’s work can be found on the website.